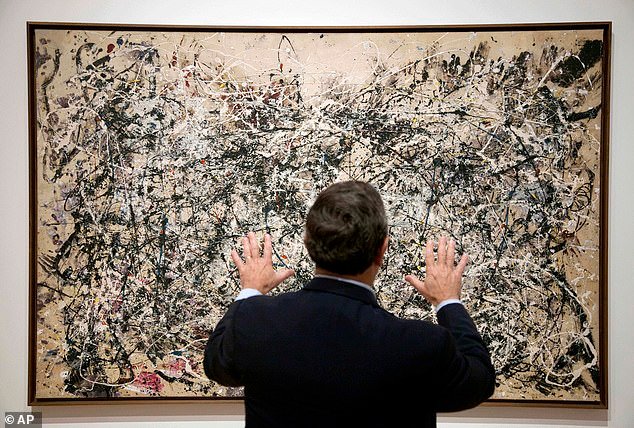

It is one of his most famous paintings and a stunning showcase of his distinctive “drip” technique.

“Number 1A, 1948,” which is on display at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York, is said to symbolize Jackson Pollock’s pure, unfettered creative freedom.

It features dynamic swirls of oil and enamel paint that descend from a height onto the canvas—a striking image that belies the painting’s minimalist title.

Now, 77 years later, scientists have identified the “extinct” pigment that Pollock used to create the masterpiece.

They confirm for the first time that the abstract expressionist used a vibrant shade of blue that had been unavailable for decades.

It was produced from the 1930s to the 1990s and was banned by the artistic community for fear of toxicity.

At the time of creation, Pollock—a troubled alcoholic for most of his life—was likely unaware of the dangers of paint.

But now that scientists know the exact shade, their findings offer “critical context for the preservation of his work.”

This particular painting, titled “Number 1A, 1948,” displays Pollock’s classic “droplet” style for which he became known. Around the time it was created (1948), Pollock stopped giving his paintings evocative titles and began numbering them.

“Number 1, 1948,” nearly 9 feet (2.7 meters) wide, is currently on display at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York City, where Pollock lived and studied.

As is clear from looking at the work, the paint has dripped and splattered across the canvas, creating a bright, multi-colored, and chaotic work.

Pollock even gave the piece a personal touch by adding his handprints to the upper right, similar to an autograph.

The 1948 painting “Number” is also a significant example of his “action painting,” which emphasized the physical act of painting.

A team of scholars from MoMA, Stanford University, and the City University of New York call it “one of his most iconic action paintings.”

“Ropes of color, drops of black, and pools of white are combined in the layered dynamics that define his style,” they say.

While previous work has identified red and yellow pigments in the painting, the painting’s “dynamic blue” has remained unassigned.”

To learn more, the researchers took scraps of blue paint and used lasers to scatter light and measure how the paint molecules vibrated.

Pollock, a lifelong alcoholic, died infamously after he drove and crashed his car while drunk in August 1956. Pictured creating one of his famous drip paintings

Manganese blue was also used to color cement for swimming pools, but it was discontinued in the 1990s because of suspected environmental and human toxicity when inhaled.

This gave them a unique chemical fingerprint for the color, which they have pinpointed as manganese blue, a synthetic pigment once found in artists’ paint boxes.

Manganese blue was also used to color cement for swimming pools, but this was discontinued in the 1990s due to environmental concerns and its suspected toxicity.

Saskaņā ar saglabāšanas un mākslas materiālu enciklopēdiju tiešsaistē ieelpošana vai mangāna zilā ieelpošana vai norīšana var izraisīt nervu sistēmas traucējumus.

Mangāna zilā krāsā, kas ir gaišs, debeszils zils, kas pirmo reizi izgatavots 1907. gadā, pat šodien ir neticami grūti atkārtot, sajaucot esošās krāsas.

Pētnieki arī pārbaudīja pigmenta ķīmisko struktūru, lai saprastu, kā tas ražo tik dinamisku nokrāsu.

Mangāna Blue tīrā nokrāsa ir saistīta ar “satrauktām” reakcijām molekulārā līmenī, kas filtrē bezspēcīgu gaismu un precīzi noregulē krāsu, saka eksperti.

Viņu analīze, nesen publicēta žurnālā Nacionālās zinātņu akadēmijas rakstiir pirmais apstiprinātais Pollock pierādījums, izmantojot šo konkrēto zilo.

Iepriekšējie pētījumi liecināja, ka tirkīzs no gleznas patiešām varētu būt šī krāsa, taču jaunais pētījums to apstiprina, izmantojot paraugus no audekla.

Lāzeri tiek izmantoti, lai noteiktu zilās krāsas paraugu ķīmisko pirkstu nospiedumu no Džeksona Polloka gleznas “Number 1A, 1948” Stenfordā, Kalifornijā

Tāpat kā daudzas citas viņa gleznas, Polloks, iespējams, būtu ielējis mangāna zilu tieši uz audekla no nūjas vai kannas, tā vietā, lai iepriekš sajauktu krāsas uz paletes.

Strādājot uz grīdas plašā pārveidotā kūtī Longailendā, Polloks attālinājās no tradicionālās mākslinieka eļļas krāsām un apskāva zemākas viskozitātes komerciālās emaljas krāsas, kuras varētu ielej vieglāk.

Eksperti, kas analizē Polloka tehnikas fiziku, jau ir ziņojuši, ka māksliniekam ir “dedzīga izpratne” par klasisko parādību šķidruma dinamikā, kā viņš to darīja.

Šķiet, ka Polloka tehnika apzināti izvairās no tā dēvētās “spirāles nestabilitātes” – viskoza šķidruma tendences veidot cirtas un spoles, kad to ielej uz virsmas.

Kaut arī mākslinieka darbs var šķist haotisks, Polloks noraidīja šo interpretāciju un tā vietā viņa darbu uzskatīja par metodisku.

Viņš reiz teica: “Mūsdienu mākslinieks strādā ar kosmosu un laiku un pauž savas jūtas, nevis ilustrē.”

Apmēram laikā, kad šis konkrētais darbs tika izveidots (1948), Polloks pārstāja dot viņa gleznas izsaucošos nosaukumus un tā vietā sāka tos numurēt.

Viņa sieva mākslinieks Lī Krasners vēlāk sacīja: “Skaitļi ir neitrāli. Viņi liek cilvēkiem aplūkot gleznu, kas tā ir – tīra glezna. ”