For decades, the Western was the beating heart of Hollywood mythmaking, an arena where heroism rode tall in the saddle and the frontier seemed endless. But like the real West, the genre had its sunsets. As times changed, so did the stories: moral clarity gave way to ambiguity, grit replaced glamour, and old archetypes faded into legend.

Some films closed the door with a bang, others with a whisper, but each marked a turning point, either for the genre itself or for the era of filmmaking that birthed it. These are the films this list focuses on, from blood-soaked finales to quiet elegies. These movies mark genuine endings in the history of Western cinema, making them bittersweet entries into the genre’s legacy.

‘Appaloosa’ (2008)

“Like being alone. Like being with the wrong man. Not having any money, a place to live.” By the time Appaloosa arrived in 2008, the Western was long past its heyday. So, rather than chasing overdone highs, the movie opts for a quieter, more character-driven take on the buddy lawman archetype. Ed Harris (who also directs) and Viggo Mortensen play two itinerant peacekeepers hired to bring order to a lawless town ruled by a corrupt rancher (Jeremy Irons). Rather than leaning on high body counts or operatic showdowns, the film focuses on loyalty, moral compromise, and the unspoken bond between its leads.

There’s an understated humor in their dry exchanges, a lived-in quality to their relationship that makes it feel like we’re watching the final chapter in a long, shared history. Through these characters, Appaloosa isn’t trying to redefine the Western or push into bold new territory. Instead, it’s simply giving it a dignified bow, a modern send-off to the kind of partnership-driven Westerns that once filled Saturday matinees.

‘Silverado’ (1985)

“I want to build something. Make things grow.” Released at a time when the Western was considered commercially dead, Lawrence Kasdan‘s Silverado felt like a joyous revival tour. It packs in all the classic pleasures of the genre: saloon brawls, cattle rustlers, quick-draw duels, and wide-open landscapes. But it does so with a knowing wink, embracing the fun without trying to reinvent the wheel. It helps that the ensemble cast is studded with stars of the decade, including Kevin Kline, Scott Glenn, Danny Glover, and Kevin Costner.

It all adds up to a bright, fast-paced flick, filled with camaraderie, standing in deliberate contrast to the grim revisionism of the ’70s and early ’80s. Yet its very exuberance marks it as a swan song for the old-fashioned adventure Western; Hollywood wouldn’t produce many more films like it. It’s both a tribute to and a last hurrah for a style of Western that had been riding into the sunset for decades.

‘The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance’ (1962)

Liberty Valance’s the toughest man south of the Picketwire…next to me.” By 1962, John Ford had spent decades shaping the Western. With The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, he began dismantling it. The film, shot in stark black and white, tells the story of a senator (James Stewart) returning to the frontier town where his reputation was forged. Through flashbacks, we learn that his rise to fame hinged on the death of outlaw Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin), a killing credited to Stewart’s character but in reality carried out by John Wayne’s rougher, more capable rancher.

The story’s moral is summed up in the famous line: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” Ford uses the film to question the very myths he once celebrated, showing that history often chooses the cleaner story over the messy truth. It becomes a statement on the Western as fantasy. For this reason, Liberty Valance was something of a turning point for the genre, marking the shift from celebratory tales to self-aware deconstructions.

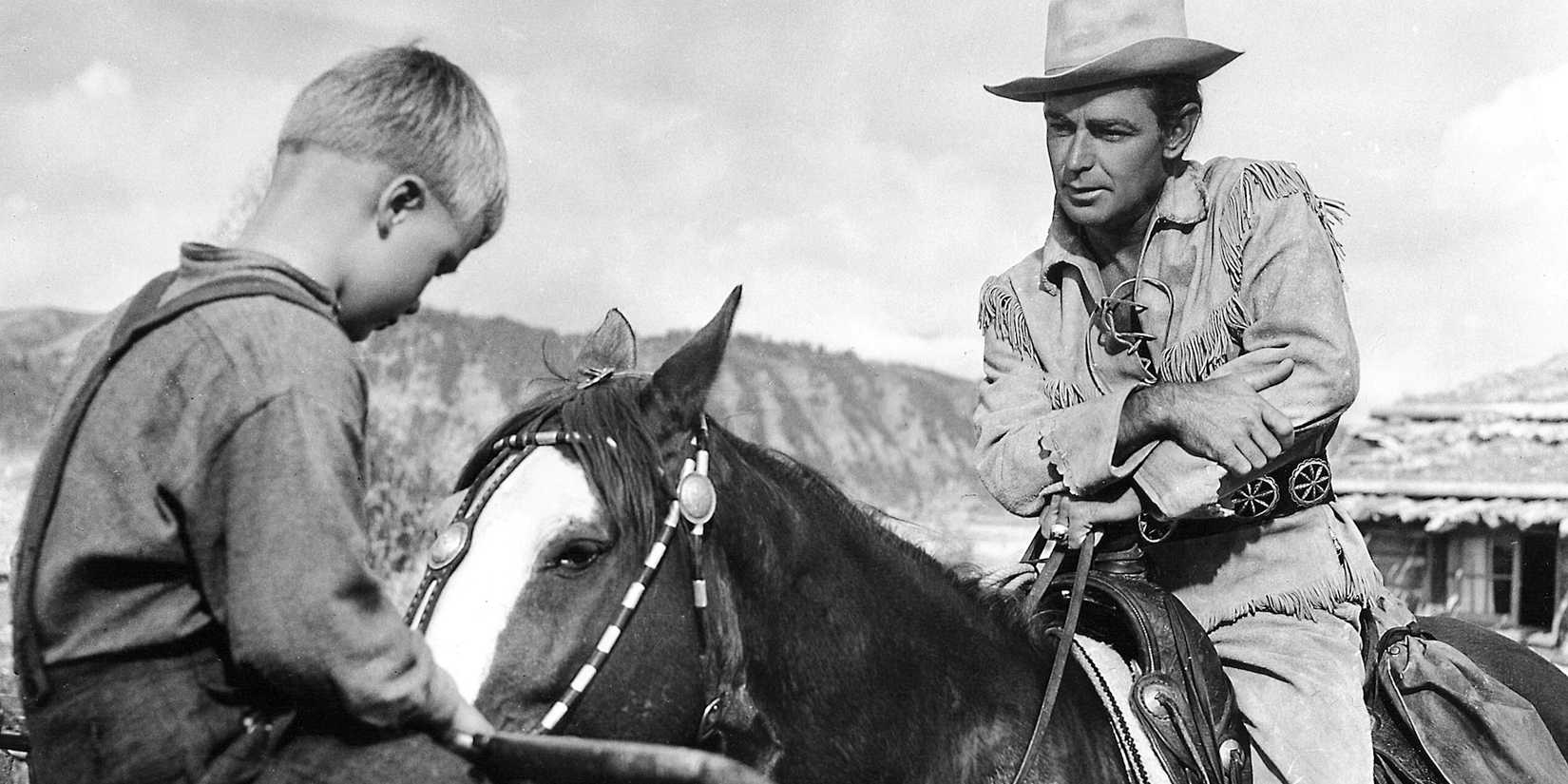

‘Shane’ (1953)

“A gun is a tool, Marian; no better or no worse than any other tool.” Shane may be one of the most enduring examples of the Golden Age Western, but even in 1953, it carried a note of finality. It tells the story of a mysterious gunfighter (Alan Ladd) who tries to leave his violent past behind, only to be drawn into a conflict between homesteaders and a ruthless cattle baron. It’s a classic narrative arc, but one told here with more emotion than usual.

Its sunlit landscapes and earnest performances embody the old-fashioned Western ideal, yet Shane himself is a tragic figure, too dangerous to remain in the peaceful community he helps save. The famous final scene, where young Joey calls “Shane! Come back!” as the gunfighter rides into the mountains, is as poignant as it is iconic. The film signaled that the age of purely heroic Westerns was ending, soon to give way to more complex and conflicted portraits.

‘McCabe & Mrs. Miller’ (1971)

“Sometimes when I take a look at you, I just keep looking and a-looking.” Robert Altman‘s McCabe & Mrs. Miller is one of the most radical reimaginings of the Western ever made, a pioneering work of revisionism. Instead of sun-baked deserts and square-jawed heroes, we get snow-covered streets, muddy boots, and a pair of deeply flawed protagonists: McCabe (Warren Beatty), a gambler with dreams bigger than his abilities, and Mrs. Miller (Julie Christie), a savvy businesswoman who runs a brothel while battling her addictions.

By using them as the focus, Altman strips the genre of its clean moral lines, replacing them with the grit and ambiguity of real frontier life, underscored by Leonard Cohen’s melancholy ballads and the bleak violence. In other words, the movie embraced the New Hollywood sensibility and rejected old-school Western romanticism. In doing so, it helped redefine the genre’s tone for a generation, showing that the West could be a place of quiet despair as much as adventure.

‘Red River’ (1948)

“You should have let ’em kill me, ’cause I’m gonna kill you.” In the immediate postwar years, Westerns were still dominated by clear-cut heroes and villains, but Red River hinted at the genre’s future complexity. Directed by Howard Hawks, it follows Thomas Dunson (John Wayne), a domineering rancher leading a cattle drive to Missouri, and his adopted son Matt (Montgomery Clift, in his debut), whose growing independence challenges Dunson’s authority.

Wayne’s character is decisive and strong as usual, but he’s also stubborn, flawed, and dangerously uncompromising, traits that would pave the way for the morally ambiguous heroes of later decades. Likewise, the tense interpersonal drama creates a bridge between the idealized Westerns of the 1930s and ’40s and the psychologically driven revisionism that would follow. Indeed, Red River is both an adventure and a character study. Its themes of intergenerational change also take on a kind of meta quality, commenting on the shifting genre itself.

‘Heaven’s Gate’ (1980)

“You’re a rich man with a good name. You only pretend to be poor.” Heaven’s Gate tells the tragic story of the Johnson County War, in which wealthy land barons wage a campaign against poor immigrant settlers. With Kris Kristofferson, Christopher Walken, and Isabelle Huppert leading the cast, the film is visually stunning, meticulously recreating its late-19th-century setting with painterly detail. Yet it’s remembered less for its plot than for its tortured creation and weak reception.

Fresh off the Oscar-winning success of The Deer Hunter, director Michael Cimino received a gargantuan budget for this project, but he struggled to wrangle it into a cohesive whole. The production problems are now infamous, and the movie’s disastrous box office performance contributed to the downfall of United Artists. As a result, for many, Heaven’s Gate is remembered as the film that destroyed an era, the grand, risky age of auteur-driven, big-budget studio filmmaking.

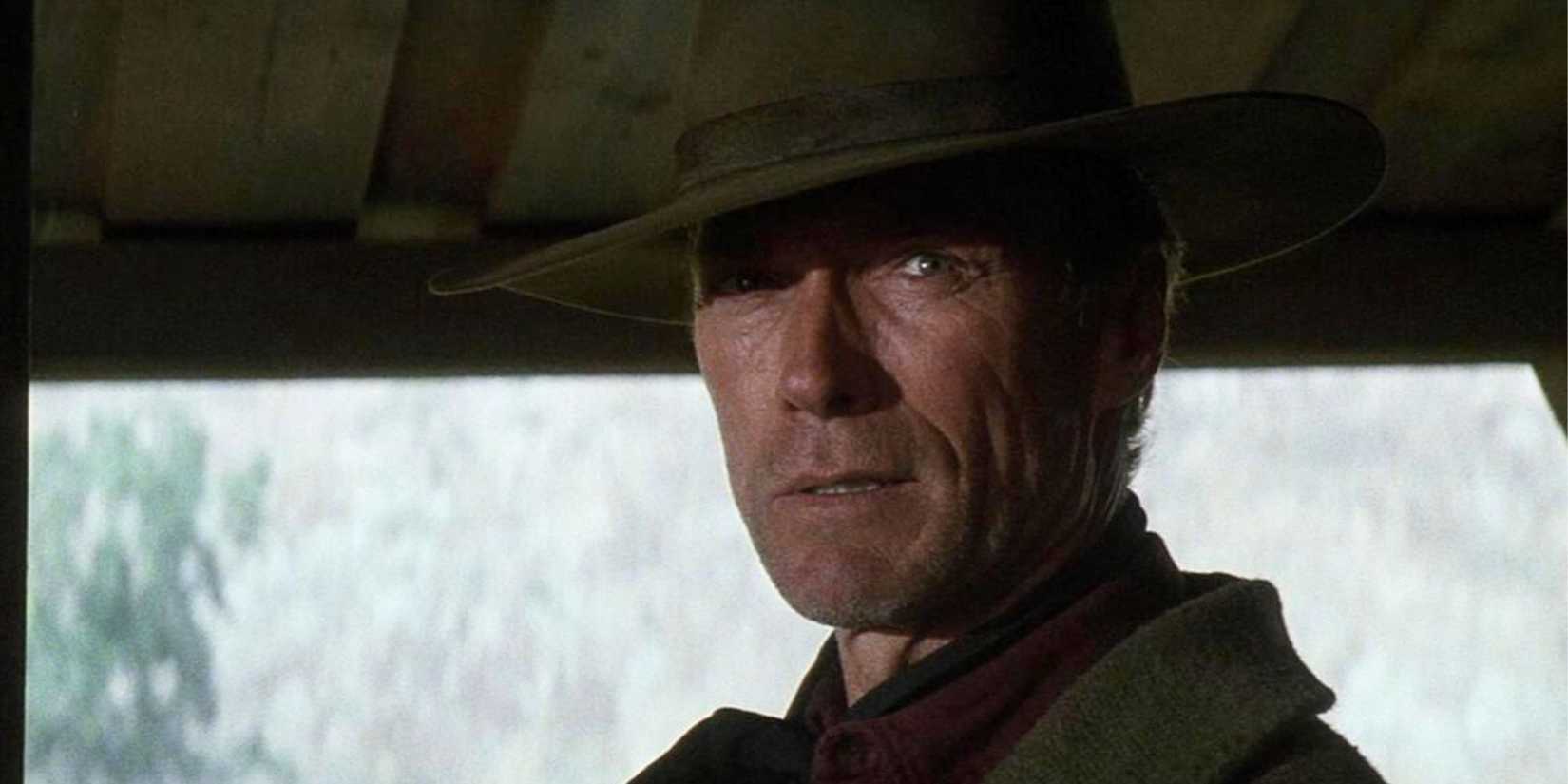

‘Unforgiven’ (1992)

“It’s a hell of a thing, killing a man.” With Unforgiven, Clint Eastwood closed the book on the gunslinger myth he had helped popularize. The movie is a farewell to a particular kind of Western and to the director-star’s career within the genre — Eastwood hasn’t made a Western since. Playing William Munny, a once-notorious outlaw now living a quiet, hardscrabble life, Eastwood crafts a story about age, regret, and the brutal realities of violence. There is no glory in Munny’s return to killing, only necessity, desperation, and an inevitable slide back into old ways.

Through him, Unforgiven dismantles the heroic illusions of the West. Even just violence is corrosive in this tale. The finished product is a compelling Western but also arguably the genre’s last great self-examination, acknowledging its lies before laying them to rest. Only someone like Eastwood, who had a long history with the genre, could have made it.

‘Once Upon a Time in the West’ (1968)

“There are many things you’ll never understand.” If The Good, the Bad and the Ugly was Sergio Leone‘s playful peak, Once Upon a Time in the West was his elegy. Released on the cusp of the Western’s decline, every frame feels like a goodbye: to the gunslinger, to the wide-open frontier, to the Western as audiences had known it for decades. The pacing is deliberate (particularly in the famous opening), and the tension is built more through silence and stares than gunshots.

Ennio Morricone‘s unforgettable score deepens the film’s operatic grandeur, making it as much a requiem as a revenge tale. Here, Leone blends myth and history, telling a story about the encroachment of the railroad and the industrial age, while focusing on archetypal figures: Henry Fonda as a sadistic killer, Charles Bronson as the harmonica-playing avenger, and Claudia Cardinale as a woman trying to survive amid violence and greed.

‘The Wild Bunch’ (1969)

“We’re gonna stick together, just like it used to be!” By the end of the 1960s, the old romantic vision of the West was dead, and The Wild Bunch buried it in a storm of bullets. Sam Peckinpah‘s masterpiece takes place in 1913, when automobiles and machine guns are beginning to outpace horses and six-shooters. The titular gang is comprised of outlaws out of time. The violence they endure (and inflict) is choreographed in operatic slow-motion and drenched in blood. It was unusually brutal for its time, even shocking.

Beneath the brutality, however, is a deep sense of loss: for friendship, for honor, and for a world that never really existed the way the legends claimed. As they march toward their suicidal last stand, the Bunch personify the end of the Old West, ushering in a new era of cinema that was grittier, bloodier, and far less forgiving. Their story marked the end of one mode of storytelling and the start of another.