The 1950s were a varied decade for film, including both old-fashioned spectacles and bold artistic leaps. Directors across the globe were redefining the medium in fascinating ways. Out of postwar trauma came radical shifts in style, tone, and ambition. Some filmmakers embraced grandeur and maximalism, while others stripped things down to moral essentials.

The result? More than a few classics. The movies on this continue to shape how we think about movies today. They represent the sharpest edges and the deepest emotions of the era. These are the era’s lightning strikes of cinematic genius.

10

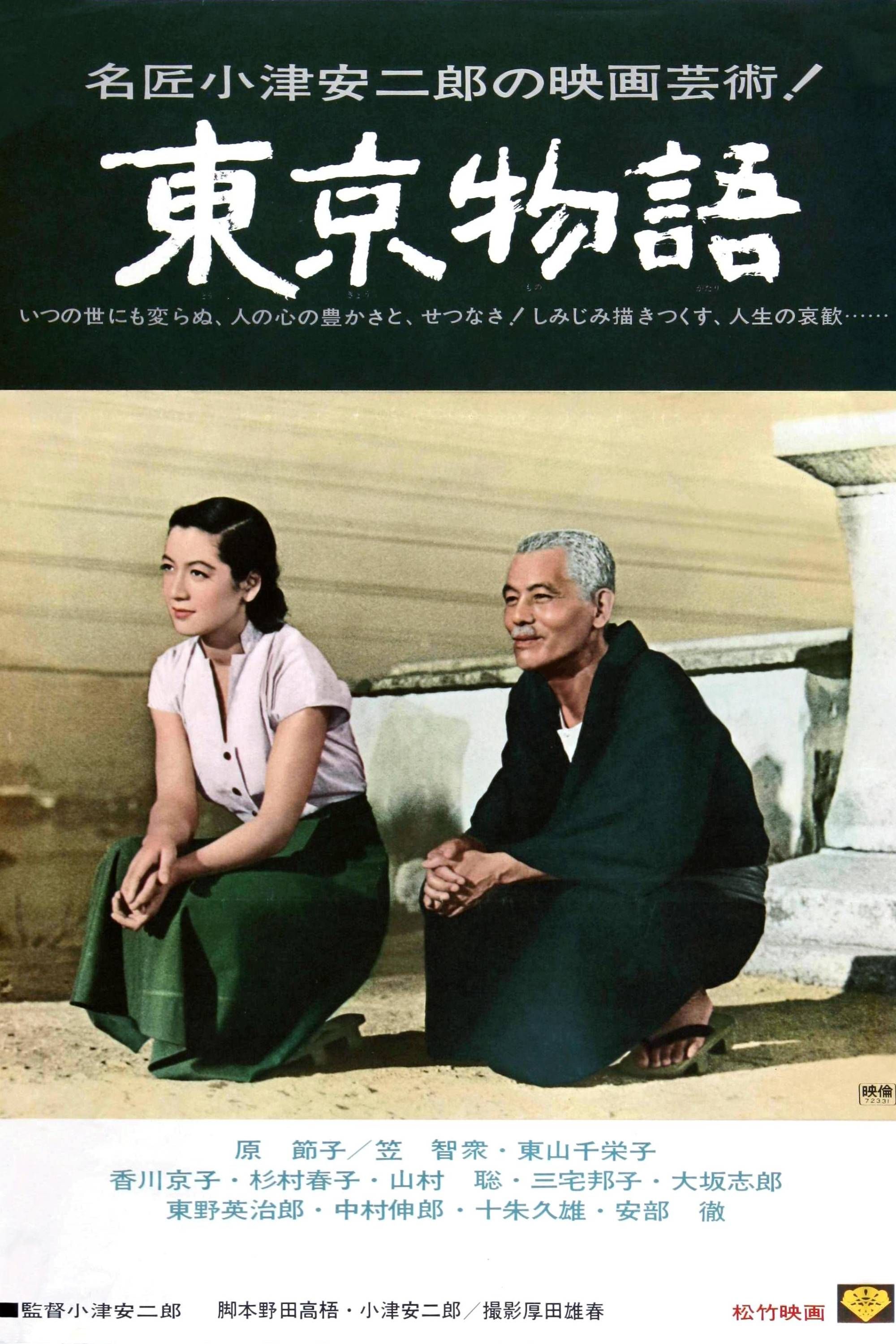

‘Tokyo Story’ (1953)

Directed by Yasujirō Ozu

“Isn’t life disappointing?” It’s quiet. Almost unbearably so. But Tokyo Story doesn’t need volume to devastate. Yasujirō Ozu‘s masterwork follows an elderly couple (played by Chishū Ryū and Chieko Higashiyama) who visit their adult children in the city, only to find themselves gently ignored, politely dismissed, and ultimately forgotten. Ozu uses this setup to make a poignant statement on time passing and people drifting apart. It’s a film about disappointment, and yet it’s never bitter. Just brutally honest.

The director’s signature low-angle compositions and still frames are deployed to great effect here. Everything is understated: the emotions, the conflict, even the grief. But by the end, when a daughter-in-law offers kindness that the couple’s own children couldn’t, the simplicity lands like a hammer. All in all, Tokyo Story is a masterpiece of restraint, and maybe the saddest movie ever made without a single raised voice. It delves deep into aging, family, and the silence that sometimes stretches between love.

9

‘The Night of the Hunter’ (1955)

Directed by Charles Laughton

“Children, do you know the devil has blue eyes?” The Night of the Hunter is a noirish fairy tale where the Big Bad Wolf wears a preacher’s collar, and bedtime stories end in murder. Charles Laughton‘s only directorial effort is a one-of-a-kind vision; expressionistic, lyrical, and seething with dread. Robert Mitchum‘s performance as the fanatical Reverend Harry Powell is brilliant. He’s a killer who stalks two orphaned children downriver with hymns on his lips, twisting scripture into a weapon.

Yet what makes the film unforgettable isn’t just its horror, but its visual poetry, particularly the stark shadows and ghostly imagery. The Night of the Hunter exists in its own cinematic universe, part Southern Gothic, part silent movie, part nightmare. It bombed on release and was misunderstood for decades. But today, it’s rightly revered as a twisted, beautiful elegy to childhood, terror, and the thin line between faith and fanaticism.

8

‘A Man Escaped’ (1956)

Directed by Robert Bresson

“Victory belongs to the most persevering.” No film has ever made silence feel this loud. In A Man Escaped, Robert Bresson tells the true story of a French Resistance fighter (François Leterrier) planning his escape from a Nazi prison, but he does it with an ascetic precision that borders on the spiritual. There’s almost no music, no melodrama, and barely any dialogue. What remains is pure, distilled tension. The limited elements are all perfectly calibrated. Every creak of a floorboard, every scratch of a spoon against stone becomes a thunderclap.

Bresson rejects conventional performance in favor of gesture, routine, and minute detail. And somehow, that minimalism elevates the suspense rather than diminishing it. As a result, this is less a thriller than a meditation on freedom, on what it means to believe in the possibility of release even in the face of death. It’s about keeping your inner life intact when the world tries to erase you.

A Man Escaped

Release Date

August 26, 1957

Runtime

101 Minutes

-

-

Charles Le Clainche

Fontaine

-

Maurice Beerblock

Blanchet

-

Roland Monod

Priest of Leiris

7

‘The 400 Blows’ (1959)

Directed by François Truffaut

“I’ve known for a long time that my parents didn’t love me.” Few endings are as haunting as the final freeze frame of The 400 Blows. It’s the birth cry of the French New Wave, announcing the arrival of one of the movement’s most revolutionary directors. François Truffaut‘s semi-autobiographical debut tracks a boy named Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud) through a minefield of neglect and harsh discipline. Léaud gives a performance that feels almost too real, fully believable as someone trapped in a world that doesn’t understand him.

More than a stock coming-of-age story, The 400 Blows is a quiet scream against institutional cruelty and parental indifference. The aesthetics reflect this. The camera is alive, playful, and wounded, conveying the defiance and desperation of its protagonist. The visual language is deceptively layered, drawing on a deep well of references and inspirations. Ultimately, The 400 Blows is as much about cinema as it is about childhood.

6

‘Wild Strawberries’ (1957)

Directed by Ingmar Bergman

“Sometimes I think I’ve lived my life just the way I dreamed it—and other times I think I’ve only dreamed it.” Wild Strawberries is a movie about time, and how we fail to understand it until it’s almost out. This Ingmar Bergman gem follows an aging professor (Victor Sjöström) on a road trip to receive an award, but the journey turns inward. Dreams, regrets, memories, and ghosts all rise to the surface. From here, the film shifts effortlessly between reality and reverie, never losing emotional clarity.

At its heart, it’s a reckoning, a man looking back at his life and asking if he was ever truly alive in it. Sjöström rises to the occasion with a stirring, mournful performance. And, on the directing side, Bergman, usually known for his bleakness, offers something close to grace. Wild Strawberries aches with sadness but glows with the possibility of reconciliation. It’s a statement on memory, mortality, and the long shadow of the choices we made. Or didn’t.

Wild Strawberries

Release Date

December 26, 1957

Runtime

91 Minutes

-

Victor Sjöström

Dr. Eberhard Isak Borg

-

-

Ingrid Thulin

Marianne Borg

-

Gunnar Björnstrand

Dr. Evald Borg

5

‘Sunset Boulevard’ (1950)

Directed by Billy Wilder

“I am big. It’s the pictures that got small.” Bitter, biting, and bathed in shadows, Sunset Boulevard is both a film noir and the most savage Hollywood satire ever made. Gloria Swanson‘s Norma Desmond is one of cinema’s greatest tragic figures, a faded silent film star clinging to past glory, locked in a mansion where time has collapsed and reality is optional. Her descent into delusion is framed by the corpse of Joe Gillis (William Holden), a jaded screenwriter who narrates the whole film from beyond the grave.

All this adds up to a story of decay simultaneously moral, spiritual, and cinematic. Billy Wilder directs with just the right balance of venom and elegance, peeling back the studio gloss to reveal a world of broken dreams and withered egos. Every line is a quote, every frame a death mask. The finished product is a funeral for old Hollywood, held with full costume and orchestra.

Sunset Boulevard

Release Date

August 10, 1950

Runtime

110 Minutes

-

William Holden

Joe Gillis

-

Gloria Swanson

Norma Desmond

4

‘Paths of Glory’ (1957)

Directed by Stanley Kubrick

“There are few things more fundamentally encouraging and stimulating than seeing someone else die.” Paths of Glory might be Stanley Kubrick‘s angriest film, and that’s saying something. Set during World War I, it’s the story of three French soldiers chosen to die as scapegoats after a failed attack, and the colonel (Kirk Douglas) who fights to save them. The real enemy here isn’t the opposing Germans but the generals, the chain of command, and the absurdity of a system that treats lives like pawns.

Here, Douglas burns with righteous fury, but he’s up against a machine too brutal to be swayed by decency. In terms of the visuals, Kubrick’s camera tracks down marble hallways like a predator, getting up close to the carnage. There’s no sentimentality in it. For all these reasons, Paths of Glory remains one of the most blistering anti-war statements ever put to film, and it showed early on that Kubrick was a major force.

3

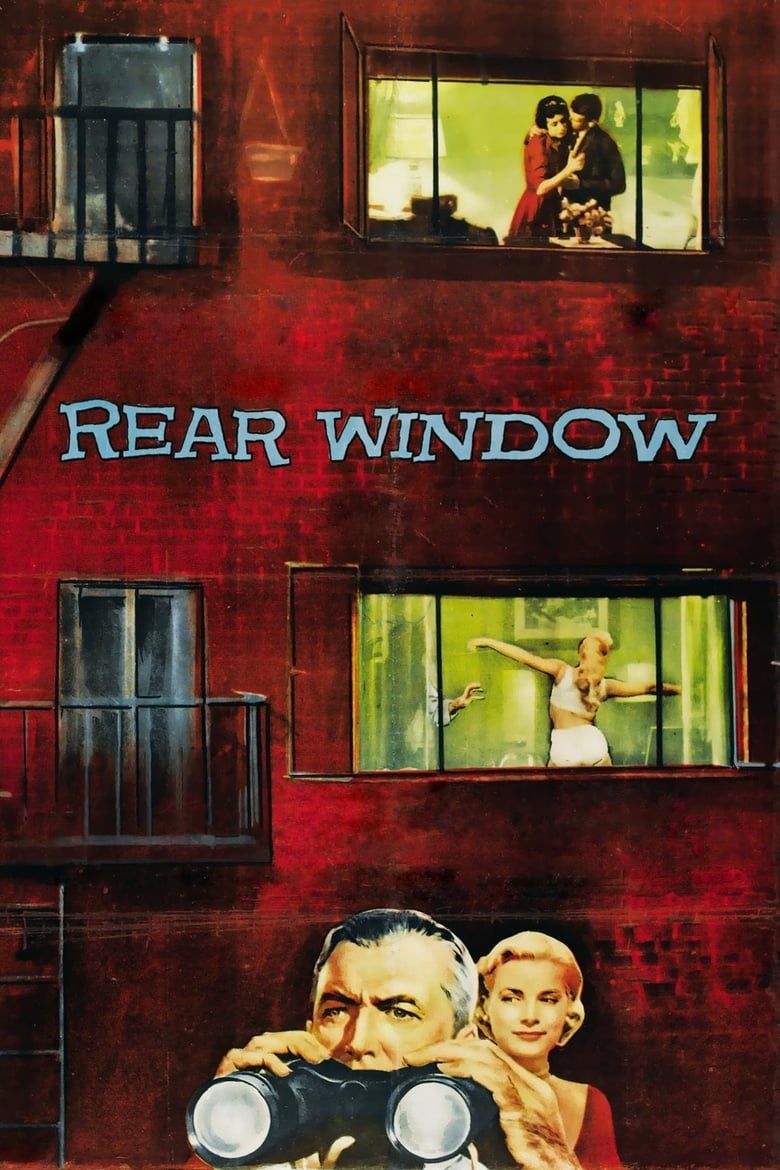

‘Rear Window’ (1954)

Directed by Alfred Hitchcock

“Intelligence. Nothing has caused the human race so much trouble as intelligence.” Few thrillers are this tight as Rear Window and none are this voyeuristic. It traps both its protagonist and its audience inside a Greenwich Village apartment, watching the world through a telephoto lens. Jimmy Stewart‘s Jeff is laid up with a broken leg and starts suspecting that one of his neighbors may have murdered his wife. What follows is pure Hitchcock: tension wound to the breaking point, then released with surgical precision.

Opposite Stewart, Grace Kelly, luminous and sharp, adds elegance and friction to Jeff’s cynicism. And the set design alone, an entire courtyard built on a soundstage, teeming with lives and secrets, is a remarkable work of craftsmanship. But beneath the style and suspense is a darker question. Why are we so compelled to look, even when we shouldn’t? It’s a commentary on the medium itself, a study in surveillance, obsession, and the morality of watching.

Rear Window

Release Date

September 1, 1954

Runtime

112 minutes

-

James Stewart

L.B. ‘Jeff’ Jefferies

-

2

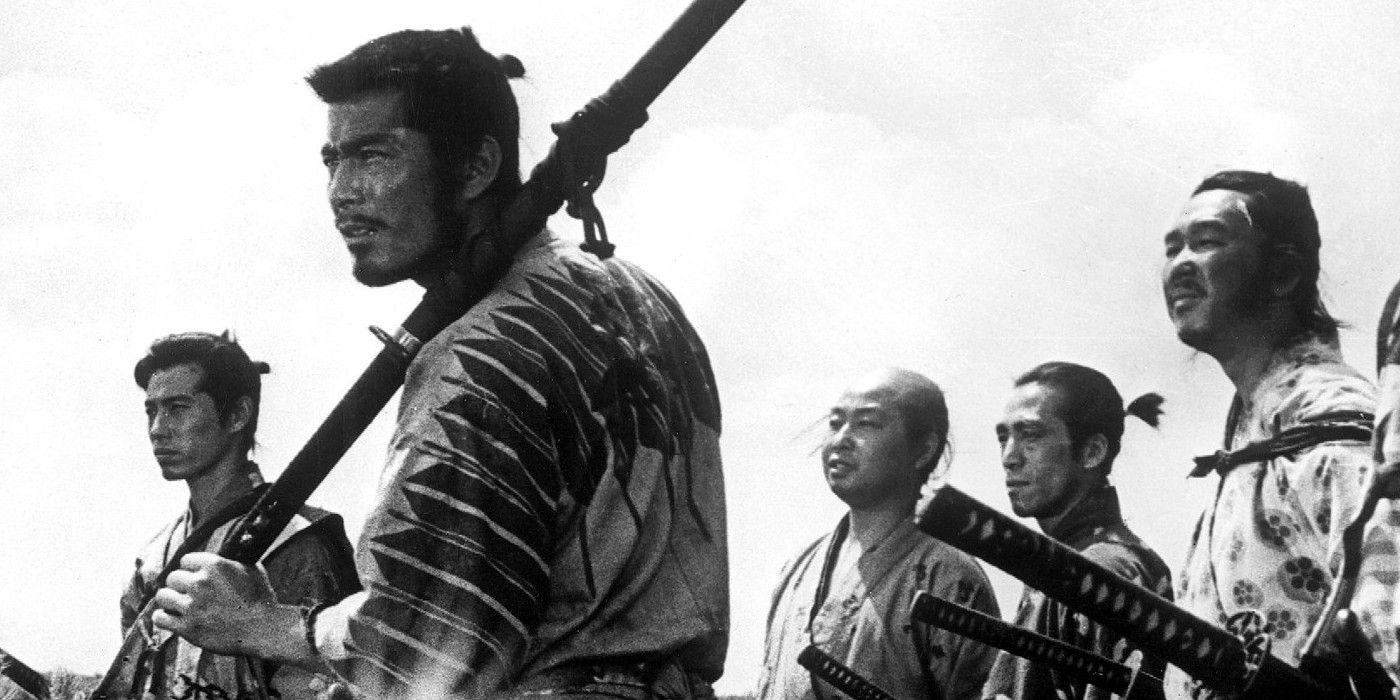

‘Seven Samurai’ (1954)

Directed by Akira Kurosawa

“This is the nature of war: by protecting others, you save yourself.” Seven Samurai contains the DNA of every ragtag team-up, every last-stand battle, and every grand redemption arc in genre storytelling. Yet what makes it transcendent is the depth of its humanity. Kurosawa‘s tale of ronin hired to protect a helpless village from bandits is a layered exploration of sacrifice, class, courage, and the cost of doing the right thing.

The action (especially the final, rain-soaked siege) is still thrilling after all these decades. But it’s the quiet moments that endure: the stolen glances, the humble gestures, the farmer’s grief. The characterization is top-notch, too. Each of the seven samurai is drawn with mythic clarity, yet each also feels deeply real. They’re fallible, haunted, and, in a way, kind of noble. Kurosawa finds space for all of them to breathe. Seven Samurai runs over three hours, but never wastes a second.

1

’12 Angry Men’ (1957)

Directed by Sidney Lumet

“It’s not easy to raise my hand and send a boy off to die without talking about it first.” One room. Twelve men. No action, no flashbacks, no music. And yet 12 Angry Men is one of the most riveting films ever made. The stakes are high, but the tools are simple: reason, empathy, and the willingness to listen. Sidney Lumet‘s debut unfolds almost in real time, as a jury debates the fate of a teenager accused of murder. Eleven are ready to convict. One isn’t. What follows is a masterclass in persuasion, prejudice, and the slow unraveling of certainty.

It’s a movie about justice and courage, particularly the bravery required to speak up when it would be easier to stay silent. Henry Fonda anchors the ensemble, but every character feels lived-in, their biases bleeding through in ways that are still recognizable today. Consequently, 12 Angry Men is more than a courtroom drama. It’s a civics lesson, a character study, and a warning.