Existentialist horror movies are always popular, because people just love to feel that sense of dread and terror. There are plenty of reasons why, although it’s mostly morbid curiosity about life and its philosophical lessons; people have lived and died for the purpose of finding life’s meaning . Existentialist horror doesn’t really scare with monsters or gore (although some films do); they unsettle you by removing meaning, certainty, and comfort.

Furthermore, existentialist horror movies aren’t simple jumpscare fests—they dissect purpose, identity, freedom, death, all the philosophical stuff that keeps you awake and alert long after the credits . This fear, the philosophical fear, is the core of existentialist horror, and the ten scariest existentialist horror movies tackle the massive task with scary precision.

10

‘Stalker’ (1979)

Andrei Tarkovsky is a cinephile’s favorite filmmaker, and although he was an open secret for a long time, more and more people are getting into his movies, mainly because their themes are, again, becoming more relevant and resonant. While Stalker may not fully qualify as a horror movie, it’s a thriller with deep-seated existential themes and psychological dive-ins. Stalker reveals to us a scary notion that wanting something might reveal the hollowness of ourselves , emphasized by long takes that make time itself feel like a weight around the neck. There are no answers, you just need to sit there and come up with your own.

Stalker is about a guide only known as Stalker ( Alexander Kaidanovsky ) to people, who leads people into a mysterious area called “The Zone”; this time, he’s joined by a writer ( Anatoly Solonitsyn ) and a professor ( Nikolai Grinko ). The Zone contains the Room, where people can enter and have their deepest wishes and desires come true . The trio travels across a desolate and dangerous landscape, learning about themselves and their lives as they look forward to entering the Room. Although not technically horror, we can let Stalker slip by, as it’s heavily existential and often terrifying, but not always for the obvious reasons.

9

‘The Seventh Seal’ (1957)

Ingmar Bergman ‘s most famous film, The Seventh Seal , also cemented his international fame. His movies overall became loved and revered, but The Seventh Seal is almost like a synonym for his name. Another movie that’s not really a horror but possesses all the qualities of one, The Seventh Seal is the quintessential cinematic meditation on mortality , doubt, and the silence of God. A lot of it is staged as a play (and it was initially written as one), and goes all out on visual appeal and dialogue-heavy performances. Max von Sydow and Bengt Ekerot enter a chess game with a dire outcome.

The Seventh Seal is about a knight, Antonius Block (von Sydow), who encounters the personified version of Death (Ekerot) and challenges him to a game of chess. Death agrees, and Block becomes convinced he can stay alive the longer the game takes. Block’s search for meaning, God, and proof of life’s value are hindered by Death’s hands; defeating it can never work. The film’s name is derived from the Book of Revelation, which talks about the end of the world, signifying that the film’s events are the end of Block’s world.

8

‘Don’t Look Now’ (1973)

Nicholas Roeg‘s 1973 psychological horror, Don’t Look Now, stars Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie, and it’s one of the earliest examples of how fragmented editing, distinct visuals, and impressionist approach can make a movie iconic and haunting at the same time. It’s a character study and a dive into the psychological dissolve of parents who’ve lost a child, both in how they relate to each other amid the tragedy and how they handle grief and pain on their own.

After losing their daughter in a tragic accident, John and Laura travel to Venice for John’s new job. While there, they meet two sisters who tell them their daughter’s spirit is trying to contact them, and John begins seeing mysterious signs and omens that hint that the past hasn’t let go. Don’t Look Now mainly shows how the couple grieve, their moments of guilt and rediscovered romance, but there’s also plenty of wonder about what’s real and what isn’t; the existential dread creeps in and is intercut with moments of tenderness between John and Laura. The devastating ending makes the existential crisis of the entire movie come full circle.

7

‘The Wicker Man’ (1973)

The Wicker Man is one of the best folk horror movies ever made, and an inspiration for all other folk horrors that came after. The eerie atmosphere of the film is paired with the protagonist’s realization that his moral code and worldview are useless in the community he finds himself in. Much like him, the viewers of the time most definitely upheld certain moral standards, and the film, which takes place on an island, really makes the protagonist feel isolated—which in turn isolates the viewer. We’re the officer visiting a mysterious community, and the movie takes all our expectations and flips them on their heads, causing existential dread and terror.

The Wicker Man follows the upright and just Sergeant Neil Howie (Edward Woodward), who is sent to investigate the disappearance of a missing child on the remote island of Summerisle. There, he meets its mysterious and secretive residents, including their eccentric leader, Lord Summerisle (Christopher Lee). Howie witnesses strange customs on the island amid the May Day celebration preparations; the rituals they perform range from bizarre to unsettling. The ultimate existential blow is the final ritual, where fear is embodied and felt throughout, and there’s really no explanation that will make sense. It is what it is, and how it is, and accepting the terror of such a fact is the hardest part of all.

6

‘Annihilation’ (2018)

Annihilation was based on Jeff VanderMeer‘s book trilogy, specifically the first book of the same name. The novel was written in first person and in the form of a diary of the protagonist; the film approaches the protagonist closely, but also follows a team of scientists as they investigate a mysterious zone that mutates biology and expands rapidly, defying time. The existential dread of Annihilation lies in its distortion of time—when we witness things evolving faster and right in front of our eyes, what ideas do we get about our own existence?

Annihilation follows a team of scientists led by Dr. Ventress (Jennifer Jason Leigh), but the protagonist is Lena (Natalie Portman), part of the science team whose husband is the only survivor of a mission into the biological mystery zone known as Shimmer. Shimmer has been overtaken by an alien force that mutates biology, and Dr. Ventress and the team’s mission is to find out what happened to Lena’s husband’s expedition. This nihilistic film weaves together curiosity with existential dread, emphasizing the human affinity for self-destruction. The movie is visually stunning, displaying the Shimmer as a beautiful but deadly space, and Alex Garland‘s habit of creating bold sci-fi horror particularly stands out here.

5

‘Eraserhead’ (1977)

Eraserhead is often considered David Lynch‘s greatest movie, even if it is his first feature-length film. The movie’s atmosphere evokes existential dread on its own, but the story also examines existence and all its beauties and absurdities. Lynch did the sound design himself, together with the surreal visuals to create an atmosphere of constantly feeling uneasy. Knowing that the works of Franz Kafka inspired Eraserhead should be enough—discomfort in one’s physical body, existential angst, and the meaning of life are all hallmarks of Kafka’s work, and now Eraserhead, too.

Eraserhead follows Henry (Jack Nance), whose girlfriend, Mary (Charlotte Stewart), gives birth to a baby that looks disfigured and inhuman. Mary leaves Henry to care for the baby himself, and he begins experiencing strange hallucinations and visions. The soundscape was designed to be anxiety-inducing, making viewers uneasy about genuinely just existing. As Henry tries to take responsibility for the baby, his life loses a sense of meaning and coherency, giving a claustrophobic and intense feeling that reproduction itself is a baseless act. Eraserhead is one of the most dread-inducing existentialist horrors out there.

4

‘Hereditary’ (2018)

Hereditary is Ari Aster‘s feature film debut, and he entered the existentialist horror plane with rave reviews. The name, Hereditary, refers to an inherited doom, the idea that one’s fate has already been written by their family ties. Hereditary is quite eerie and has an intense atmosphere throughout, making viewers worried about what might happen next. This, paired with jolts of physical horror, makes the movie’s existential despair feel inescapable.

Hereditary follows the Graham family: miniature artist, Annie (Toni Collette); her psychiatrist husband, Steve (Gabriel Byrne); their teenage son, Peter (Alex Wolff); and young daughter, Charlie (Milly Shapiro). Annie’s reclusive mother, Ellen, dies and Annie reveals to a bereavement group that she had a difficult life which rarely involved Ellen—until Charlie was born; Ellen’s involvement with the occult and the supernatural seals the family’s fate. While themes of grief and mourning are interspred, Hereditary is also a family drama. Colette delivers an Oscar-worthy performance, and will remain memorable for Annie, in particular the “I am your mother” speech at the dinner table.

3

‘Pulse’ (2001)

There’s an array of brilliant Kiyoshi Kurosawa movies that you could easily turn into a movie marathon, but tread lightly as most are somewhat existential and doomy. Pulse is one of them, an existentialist horror that will make you sit in the dark several minutes after it ends just to digest the bleak, terrifying message it delivers. It’s also an interestingly timely and relevant movie, because it predicted and analyzed how much a network-connected world can actually be disconnected. People are online, virtually social, but when the lights are off, they’re essentially alone, and that creates an unbearable weight on existence.

Pulse is set in Tokyo at the turn of the 21st century, showing that people are becoming more and more plugged into computers and the internet. When a series of strange suicides coincides with ghostly figures appearing through computer screens, two weaving storylines about groups of friends dealing with the apparitions begin merging into one. Pulse introduces the idea that technology and modernity are a stage for radical isolation; Kurosawa also reframes death as a sort of permanent solitude, capturing the notion that it doesn’t get any less lonely, but you’re dead.

2

‘The Lighthouse’ (2019)

In the world of existentialist horror, Robert Eggers is truly like a king; his works are all dark and toned down, but also excessively filled with existential dread. The Lighthouse is one of the darkest existentialist psychological horrors to exist, with cabin fever and mania growing stronger as isolation takes a toll on the protagonists’ sanity and egos. Paired with the 1.19:1 aspect ratio to emphasize the boxy confines of an isolated cabin, and black-and-white visuals that enhance the eroding atmosphere, The Lighthouse is a trippy journey with intense symbolism and dread.

The Lighthouse follows two lighthouse keepers, a young newcomer, Ephraim Winslow (Robert Pattinson), and an older keeper and former sailor, Thomas Wake (Willem Dafoe). As they spend their days on the island and in the lighthouse, they face mythical creatures, superstitions, and a looming mania that threatens to take over them the longer they stay in isolation. The setting immediately shows us madness is inevitable; there are some scares, but none jump out. They’ll just mostly make you feel like you’re also getting madder yourself, turning the existential knobs back onto the viewers.

1

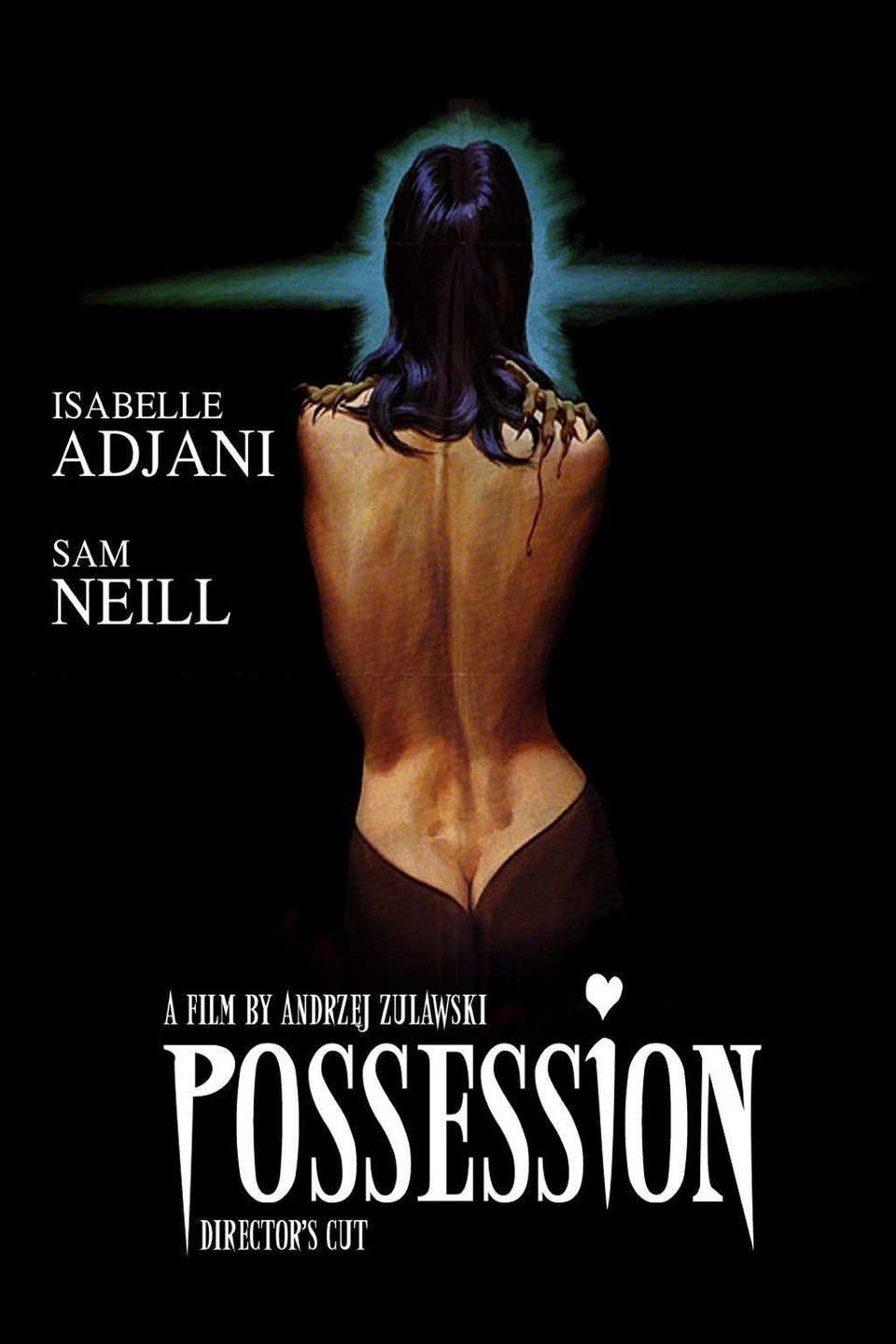

‘Possession’ (1981)

Possession is an essential horror story, filled with such existentialism, fear, and terror, that it’s just as hard to look away as it is hard to watch . We’re drawn into it, especially by Isabelle Adjani as the lead, and her convulsive performance in a pivotal scene in a subway tunnel. Her pain and madness feel palpable, even contagious through the screen, fusing body horror with supernatural, mythical, and psychological moments. She claimed herself it was a role she would never do again , recalling it with the words: “There was something of great violence that I agreed to take on.” Possession examines its heroine’s identity as much as Adjani did herself after making the movie.

Possession is about Mark ( Sam Neill ), a spy returning home from a mission in West Berlin. When he returns, he learns that his wife, Anna (Adjani), wants a divorce. Mark leaves, but Anna undergoes a physical and mental transformation that is mysterious and almost inexplicable , with Mark becoming increasingly worried. There’s some theme in there about mothers and wives dedicating their entire being to others, sometimes so much that their self slips away from under them. With intense and shaky close-ups and a great physical role by Adjani, Possession is a true existential nightmare.